A Brief History of Time Travel Films

From Groundhog Day to Terminator to Primer

The time travel genre has birthed some of the most culturally significant and highest-grossing films of all time, from Groundhog Day to Avengers: Endgame ($2.7 bn). It is a particularly important genre at this moment in time because it teaches us to live fully in the present in the face of a frightening future, escape the violence of human nature, and embrace the repetitions of daily life.

As a filmmaker gearing up to direct a time travel feature, I have been exploring these themes as well as the tropes, creative opportunities, and challenges of this fascinating genre. I’ve found that for every time travel film that exhibits a deep, evocative understanding of how humans contend with their limited time on this planet, dozens fail to resonate because they suffer from the genre’s pitfalls. These include plots that suffer from convoluted time travel timelines, an overwhelming number of time travelers whose plot arcs are difficult to track, and minor regard for the psychological effects of time travel on the main character.

The following consideration of the genre spans time travel films of silent cinema to blockbuster franchises like Planet of the Apes, Terminator, and Back to the Future. Also discussed is the post-Groundhog Day (1993) surplus of time loop films, wherein the central character is stuck in an endlessly recurring day. Edge of Tomorrow (2014), Palm Springs (2020), and Meet Cute (2022) are notable examples, some more successful than others.

Included is a deep dive into films that focus on fractured experiences in human time, such as masterpieces like La Jetée (1962) and Primer (2004), which, at their best, reflect time traveling as a universal human experience. This sensation arises because, to some degree, every person on this planet lives in the present, is caught up in their past, and obsesses over the future. These types of films enrich our grasp of this ubiquitous mental time travel condition.

The discussion concludes with an examination of time travel romances. I’ll take a close look at the additional layer of challenges posed by unifying romantic and scientific elements in Somewhere in Time (1980), The Lake House (2006), and The Time Traveler's Wife (2009). When seamlessly blended, the time travel romance produces deeply compelling cinema including the only time travel film to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture.

TIME TRAVEL IN EARLY CINEMA: BIRTH OF CONVENTIONS

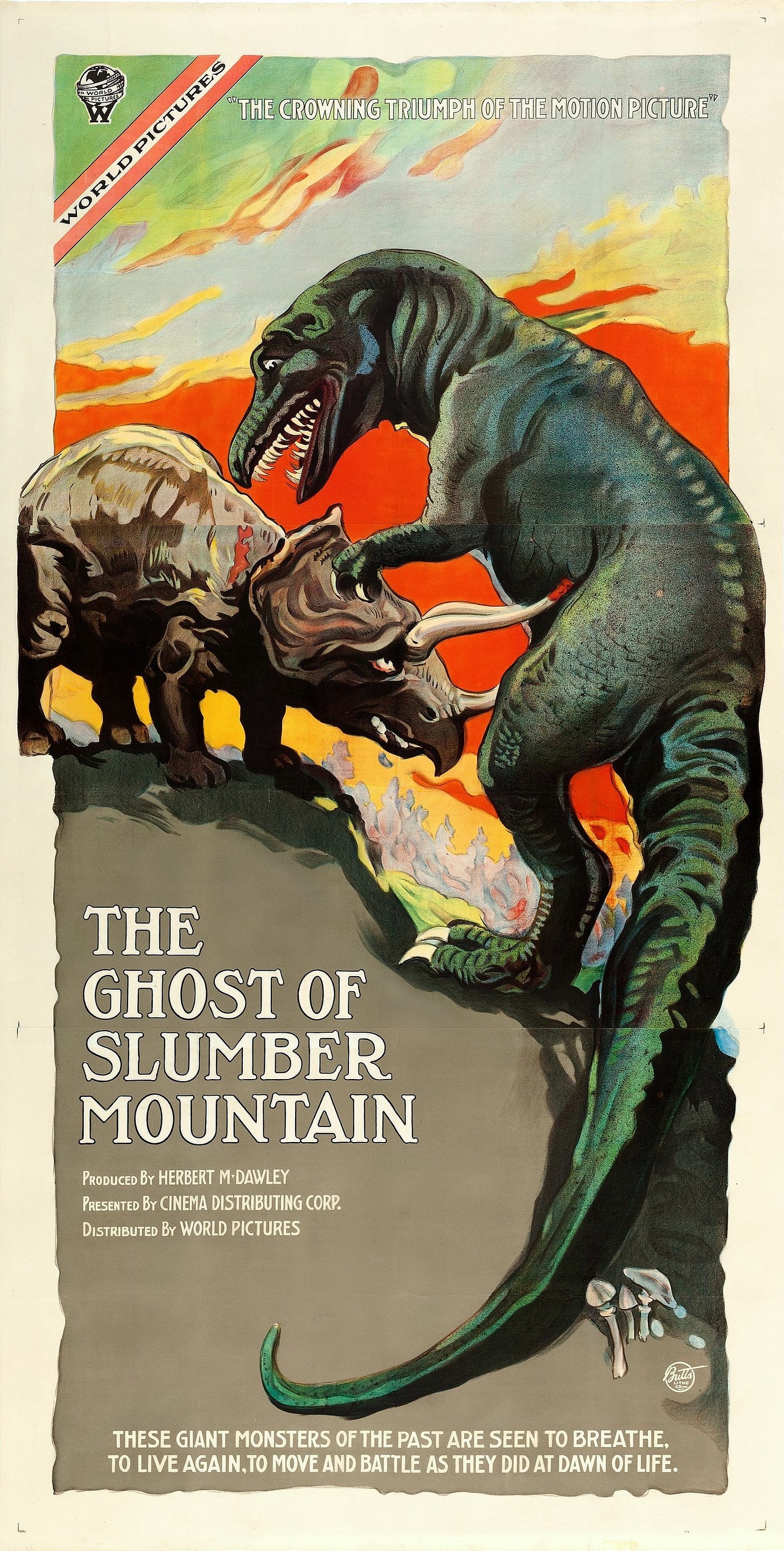

From the beginning of cinema, filmmakers transported audiences into alternate time periods with reenactments of historical events and fantasies of past eras. So it is fitting that in the first actual time travel film, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1917), the time travel device functions very much like watching a movie. In the film, two friends hike to a cabin where they discover a lens-like looking glass. When taken outside, the looking glass allows them to gaze into a prehistoric moment on Slumber Mountain: dinosaurs fighting on the summit.

Their contact with the Cretaceous period through a visual instrument, in effect, likens their experience to moviegoers of the time, for whom the cinema screen was their looking glass into past times. For these characters, the time travel machine allows access to a violent era, with the present serving as a place of security, a quality shared by other time travel films.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1921), the first of eight film adaptations of Mark Twain’s novel between 1921 and 2001 (Black Knight), positions technological advancements as a positive marker of human progress in comparison to the barbaric past.

In the film, a radio repair man wanders into a mad scientist’s laboratory. Then, he suffers a concussion that sends him back in time to King Arthur's court, where he almost gets burned at the stake. There, he outwits dangerous enemies by inventing contemporary weapons, including guns, tanks, and planes.

Unlike successive time travel films, the introduction of modern technology into the past has no negative repercussions. The efficiencies of modern instruments of war are lauded as King Arthur’s kingdom gains a vast advantage over a neighboring kingdom. The war machines of the 1920s are positioned not as destructive but as constructive instruments of peace to be celebrated.

Connecticut Yankee forged this now-common genre convention of the time traveler introducing modern technology to the people of the past/future. It was also the first film to feature an opening scene in which the time traveler, after being transported to the future/past, attempts to orient themselves by cluelessly asking when they are (not where they are), establishing a set-up still being used in the 2020s.

Additionally, it is the first film to establish a time travel paradox, a logical contradiction associated with time travel often called the “grandfather paradox.” e.g., if you went back in time and killed your grandpa, you'd prevent your birth. But if you're not born, you couldn't go back to kill him. These paradoxes, which showcase scenarios in which the lead character is not born, whether brought on by accident (Back to the Future) or by menacing forces (The Terminator), provide a narrative mechanism for protagonists to take control of their lives.

Connecticut Yankee also cemented another important convention, a mad scientist describing their time travel machine’s capabilities:

“Every sound that has been uttered is still vibrating somewhere in the ether… If I can build a set sensitive enough I can tune back into the past and hear those sounds, think of hearing Lincoln’s own voice delivering the Gettysburg Address.”

The scientist’s reference to Lincoln’s speech commemorating the Civil War’s deadliest battle is a mouthpiece for the film’s interest in themes of war and destruction. Although the film celebrates the use of modern weaponry in conquering enemies, it introduces into the genre still existing anxieties about the unchangeable destructive nature of humans. Be it modern military devices in the present, deadly Civil War artillery in the 1860s, or the primitive equipment of carnage in King Arthur’s 5th Century, Connecticut Yankee sees war as a positive marker of society’s advancement.

Later time travel films view technological advancements, especially tools of violence, very negatively such as War of the Worlds and The Terminator which showcase humanity’s unending destructive nature.

The Time Machine (1960), an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novel, focuses more pointedly on immutable cycles of human violence. In this film, the time traveler, eager to escape his era of carnage, ventures into the future but sees nothing but large-scale violence, leading him to recognize that human behavior cannot be changed, society is stuck in cycles of destruction.

The film begins in 1899 in London, with H. George Wells (Rod Taylor), the inventor of the time machine, explaining his desire to leave the present:

"I don't much care for the time I was born into. It seems people aren't dying fast enough these days. They call upon science to invent more efficient weapons to depopulate the earth."

The cynicism of the present era becomes a catalyst for many subsequent time travelers in cinema seeking the future. In the opening scene of Planet of the Apes (1968), astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) ruminates, “Does man… who sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother, keep his neighbor’s children starving?” In Time After Time (1979), another character named H.G. Wells (Malcolm McDowell) shares similar concerns: “Now why the future? Because... there'll be no more war, no crime, no poverty, and no disease either.”

These three travelers believe they can escape humanity’s destructive nature. Like all techno-utopiasts, they are future-oriented in their thinking, pushing as quickly as possible to get out of their time. This mentality is a product of the historical moment in which these films were produced: the Cold War and the Vietnam War.

For instance, in The Time Machine, traveling from 1899 into the future to 1966, Wells discovers nothing but endless war, displaying how human nature cannot be changed no matter how far technology advances. Unwilling to accept the determinative nature of the universe, Wells decides to travel much further in the future to the year 802,701. In a case of dramatic irony, Wells shifts from being a pacifist to an active participant in the continuing violence of the future, leading the human race in a battle against a sub-human group that lives below ground, extinguishing the latter race.

Although this ending is presented as rosy, Wells has had to become that which he condemned at the start: an instrument of violence. This transformation underscores that no matter how far we run from our present, we are shackled by the darkest elements of human nature—an unsettling truth that Planet of the Apes (1968) and the time-travel franchises that followed explore even more deeply.

TIME TRAVEL FRANCHISES OF THE 60s-80s: SKEWED DETERMINISM

Planet of the Apes (1968), based on a 1963 novel by French author Pierre Boulle, used time travel to suggest the inescapable essence of the present, past, and future. In the film, despite rapidly evolving technology, society remains morally stagnant, bringing out our worst nature. The first time-travel film to spawn a major franchise, Planet of the Apes, has since evolved to include ten films, grossing $2 bn worldwide. With the latest entry, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024), taking close to $400 M worldwide, the franchise continues to burgeon.

In the original Planet of the Apes, a spaceship carrying a crew of four departs in 1972 and travels close to the speed of light, returning to Earth in 3978. In the film’s opening scene, while the ship is in flight, the captain hopes, like Wells in The Time Machine, that technology can eliminate our destructive human nature. In a way, it does eliminate our “human” nature by engendering a planet of apes.

The captain encounters a planet ruled by apes, a cruel and destructive society embedded with racism, classism, and intolerance, reflecting the one he left. The condition challenges his early belief in techno-utopianism, exhibiting that humanity’s inhumanity persists despite technological progress. This is similar to The Time Machine, which has the same concerns, with a key difference being the future civilization the captain encounters in Planet of the Apes is much more detailed and, therefore, ripe for comparison to the present.

His temporal forward progress leads to a future society uncovering the most barbaric elements of our nature—we are literally speaking apes. The next time travel franchise also ruminates on elements of human and nonhuman nature, particularly in terms of the brutalities beings are capable of inflicting on one another.

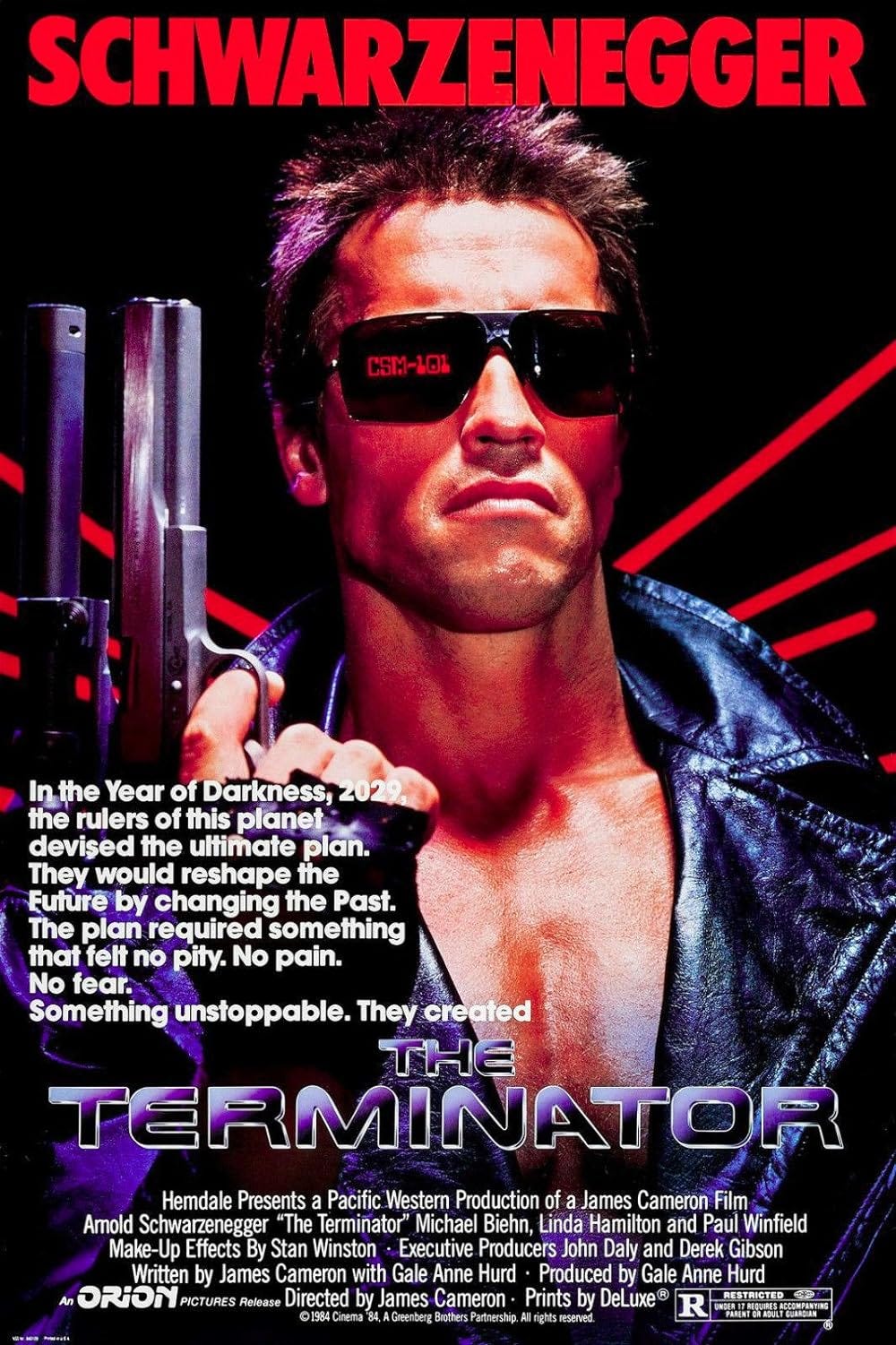

The Terminator series presents a more modern and optimistic view of where human nature is heading. It explores the value of retaining our humanity in an era when, to compete with the invention of increasingly human machines, people have made themselves more robotic. Its concerns, looking at them now, in the age of machine learning, are critical to our survival as a species. With six Terminator films grossing $1.75 bn and the recent launch of the well-reviewed animated Netflix series Terminator Zero (2024), the franchise has continued its high standing in culture.

James Cameron’s inaugural The Terminator (1984) begins with a cyborg (Arnold Schwarzenegger) using “time displacement equipment” to take a one-way trip from the post-apocalyptic future 2029 into the 1980s to kill Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton), a waitress whose future son is destined to save humanity. Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn), the only human time traveler in the film, is sent from the future to protect her.

To fight the machines of the future, Reese has had to become one: mechanized, tactical, and unfeeling. But his heroic act of traveling to the past to save Connor humanizes him. He describes his experience of time traveling as a catalyst for this transformation, “white light, pain, like being reborn maybe.” Reese likens his experience of time travel to rebirth because to go to the past, he and the other characters must enter the time machine naked. Accordingly, the film plays with the notion of human flesh, whereby each character’s identity is exposed by what’s under their skin. Connor is fully human and displays the full range of human emotions. Reese, also made of human flesh and bone, has had some of his pain centers disconnected, showing his literal detachment from what makes him human. The Terminator does not feel pain at all because under his skin is a machine.

In The Terminator, the human time traveler transforms from an unfeeling soldier to a romantic hero as Reese develops a romantic attraction to Connor. The two consummate their relationship, leading to the birth of John Connor, leader of the resistance to the machines. As the film progresses, Reese becomes more human, while the Terminator becomes more mechanical, getting stripped down, his flesh removed piece by piece until he is nothing but metal and electronics. Ultimately, Connor defeats the machine because Reese selflessly sacrifices his life so she can live, enabling her to defeat the machine, showing that society’s greatest hope is reconnecting with one’s humanity. Despite the film’s dark tones and the haunting threat of dystopia, it is one of the most optimistic films in the genre because it foregrounds the value of human potential.

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) expands on the vision that we must use our present to prevent the erosion of our humanity in the future. It highlights that the actions we take today—especially regarding technological responsibility and ethical decisions—directly shape our future world. Without care, we risk creating a dystopian future dominated by our own unchecked advancements. Unlike the bleak determinism of other time-travel movies, this film is glowingly positive that we can change our fate.

Terminator 2 is initiated by John Connor’s emblematic action: he reprograms the cyborg (Schwarzenegger) from a Terminator to a Protector. The idea that we can change who we are destined to be is a mantra that Connor lives by. She says, “The future is not set, there is no fate but what we make for ourselves.”

Although Terminator 2 (1991) is a film about humanity’s ability to guide its fate, it is also a haunting parable of training large language models. The young John Connor in Terminator 2 asks the Terminator if he can learn. The Terminator responds that he is a neural net processor, an advanced CPU, that does, in fact, learn— anticipating Open AI’s Chat GPT. Throughout the film, John Connor repeatedly trains the Terminator’s neural network by correcting his behavior to be more human, feeding it human phrases (Hasta la vista, baby!) so it can interact in a more human way. In contrast, Sarah Connor has become more machine-like in this film, hardened by her experiences in Terminator 1.

The film explores what defines humanity in an age where machines can mimic human abilities. According to Terminator 2’s more contemporary commentary, Connor and Schwarzenegger’s role reversal suggests that humanity's resistance to mechanization is not set in stone but is influenced by our resistance to blind adoption of technology. In contrast, in many previous time travel films, a common theme is that humanity is irredeemable and attempts to alter destiny through technological advancement are futile.

In terms of the film’s formal elements, the first two Terminator films succeed because they structurally limit the time travel to flash forwards. In both films, the characters are haunted by a horrible future: in Terminator 1, Reese’s memory of the war against the machines (clip), and in Terminator 2, Connor's nuclear bomb nightmare (clip). The flash forwards in these films that are otherwise grounded in the present is a crucial choice. Those films that mix mental time travel (flash forwards/flashbacks) with literal time travel often render it difficult for viewers to distinguish between the two (as in Meet Cute, discussed later).

The next two films in the series suffer from a range of weaknesses, many of which are unrelated to time travel and are therefore outside the scope of this essay, such as being overly cliche (2003’s Terminator: Rise of the Machines) or too low-stakes (2009’s Terminator Salvation).

Terminator: Genisys (2015) exhibits the worst qualities of time travel films: confusing changes in various timelines, an overwhelming number of time travelers, and a lack of interest in the psychological effects of time travel.

In this film, we see the events from the future that trigger the first Terminator movie: Schwarzenegger getting sent to the past and John Connor sending Kyle Reese back in time to save his mother. As Reese, born after Judgement Day, travels back in time, he has a very intense flashback of a life he didn’t live: an upbringing in a suburban home with loving parents. When he’s questioned if he’s remembering his future, he’s offered this confusing explanation:

“No. The boy is the alternate timeline version of you. Kyle Reese is remembering his own past, which is our future… It is possible if you were exposed to a nexus point in the time flow, when you were in a quantum field… A nexus point is an event in time of such importance, that it can arise to a vastly different future… If John Conner had to be killed or compromised, it could result in the ability to remember both pasts.”

Not only does this not clarify what is happening to Reese, but it doesn’t bring audience members closer to understanding the psychological experience of being displaced in time. Films like these (see Deja Vu) use time travel as a springboard for sci-fi action set pieces rather than dealing with the psychological effects.

Adding to the complications in the film, when Reese and the Terminator travel back in time, there is a wild flip: All the Terminators from the series are already in 1984:

Schwarzenegger from Terminator 1

Schwarzenegger “the protector” from Terminator 2

Liquid Metal Terminator from Terminator 2

Further unnecessary time travelers in Genisys are John Connor, who arrives in the past as a Terminator, and Reese, who meets himself as a child. The film features every Terminator character all at once. For this reason, it doesn’t let audiences know who they need to care about: Reese and Sarah falling in love, the duo defeating their son John, who is now a Terminator, or Sarah and the Terminator’s father-daughter relationship.

All emotional resonance gets terminated.

Terminator: Dark Fate (2019) is the best post-James Cameron sequel. The film uses its conceit of a new, dark fate to reinforce the series’ idea that our actions can change our future. It differs from T5 in almost every way. Instead of being a slave to the mythology of the previous films, it escapes it by creating a new one.

The film opens with Sarah and John Connor living carefree in Guatemala (right after the events of Terminator 1) when, out of nowhere, the Terminator kills John in cold blood in front of his mother. Smash cut to a new future 20 years later. Grace (not Kyle Reese) has been sent back in time to protect Dani (not John Connor). In the process, they encounter Sarah Connor (played by the original actress Hamilton).

Connor has calcified after witnessing the death of her son, making her machine-like (even more so than in Terminator 2). However, the events in the film allow her to understand the value of life, and she ultimately reclaims her humanity.

This is the most resonant character arc in the series: when any machine or machine-like person grows a heart. Even the Terminator, who assassinated John Connor earlier in the film, has settled down with a wife and kids. When asked if he loves his new family, the Terminator’s response captures the essence of the entire series:

“Not like a human can. For many years I thought [not being human] was an advantage. (pause) It isn't.”

The series shows us that we can either accept our fate and fall victim to emotional mechanization or actively write our destiny by choosing to embrace vulnerability. It reminds us that the true battle isn't against machines but against the emotionless isolation we self-impose on ourselves in the face of loss. Our future is not predetermined but written by those bold enough to feel.

Back to the Future (1985) is a light-hearted, playful take on the genre. The three Back to the Future films released from 1985 - 1990 grossed $964 M worldwide. This series earned the highest per-film time travel series average of $321.3 M/film. It’s not just because the characters are lovable (and they are!); the film’s characters implore each other to be the best versions of themselves, an optimistic spin on the genre that made this series a classic.

The film opens with high school student Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox), running late for class when he encounters hall monitor, Mr. Strickland, who denigrates his past and his future. Strickland smirks, “No McFly ever amounted to anything in the history of Hill Valley.”

This notion is crystalized moments later when McFly and his band get kicked out of an audition for the high school dance for being too loud. Later, McFly tags up with Dr. Emmett Brown (played by the epically zany Christopher Lloyd), who offers a great twist on the classic explanation for why he invented the DeLorean time machine, “I’ve always dreamed of seeing the future, looking beyond my years, seeing the progress of mankind, I’ll also be able to see who wins the next 25 World Series.” While most time travel franchise films make overarching statements about humanity's fate, Doc is the first mad scientist whose predilection for time travel is driven by a DIY hobbyism indicative of the Silicon Valley garage era of the 70s and 80s. It’s a more light-hearted and grounded touch.

After delivering this positive mission statement about seeking out the future, Doc Brown is killed by Libyans, forcing McFly to flee in the DeLorean, which launches him thirty years into the past. When Marty McFly goes back in time, he accidentally gets hit by a car. Originally, his shy dad was supposed to get hit and meet his mom while recovering, which helped them fall in love. By taking his dad's place in the accident, Marty changes this event.

McFly’s role in Back to the Future goes beyond just altering history; he inspires the key figures in his life. He helps his father find the courage to stand up for himself and ask out his future mother, and he gives Doc Brown the confidence to pursue his inventions, ensuring his success. In turn, Marty gains self-assurance, redeeming his botched musical audition by delivering a spectacular performance at the high school dance, setting in motion the events that lead to his parents' first kiss. Thus, McFly’s character growth prevents the Grandfather paradox, ensuring his birth.

Time travel becomes a metaphor for taking control of one's life, like in the Terminator series, but in a way that is less about the survival of the species and more about our survival in daily life. Understanding our negative behavior patterns by reflecting on our past allows us to shape our future, unlike any time travel films covered thus far, akin to Edge of Tomorrow, but in a less high-stakes environment.

Back to the Future sparked additional 1980s high school time travel films:

In Peggy Sue Got Married (1986), Sue (Kathleen Turner), on the verge of a divorce, faints at her 25th high school reunion and wakes up to find herself back in 1960, leading her to try to correct the mistakes that led to an unhappy marriage.

In Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1988), two rock-'n-rolling teens (Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter), on the verge of failing their class, set out on a quest to make the ultimate school history report after being presented with a time machine.

While the first Back to the Future is both light-hearted and significant, the sequel, Back to the Future Part II (1989), suffers from its handling of a range of formal elements that prevent it from being resonant. The first film is tightly focused on McFly correcting a single error he makes when traveling back in time (separating his parents from falling in love), but the sequel makes the mistake of having the main characters try to prevent a surplus of time errors, undermining the effectiveness of the film.

Here are eleven major time errors the characters try to correct:

2015

McFly’s kids are criminals

Older Marty McFly’s autombile accident

Older Marty McFly’s childish temper

1984

Hometown is a dystopia ruled by his enemy, Biff

McFly’s mom is married to Biff, who is now his stepfather

McFly’s father’s death

1955

Biff is gifted a sports almanac by his future self, which will make him a millionaire

McFly’s parents don’t fall in love

McFly gets jumped by bullies

McFly and Doc prevent themselves (from Back to the Future 1) from jumping forward in time with the lightning strike

1885

Doc is stuck in the Wild West

The film makes both of the common time travel mistakes also inherent in Terminator 5. First, it’s wildly hard to track what we should care about. Films like these try to up the stakes artificially by adding unnecessary layers of complexity through the mechanism of alternative futures and pasts, which prevent our investment in the characters.

Second, the language the Doc uses to describe a time travel paradox is esoteric:

“I foresee two possibilities. One, coming face-to-face with herself 30 years older would put her into shock and she'd simply pass out. Or two, the encounter could create a time paradox. The results of which could cause a chain reaction, that would unravel the very fabric of the space-time continuum and destroy the entire universe.”

Contrast that with the simple explanation Doc gives about seeing the next 25 World Series winners in the first film. Time travel is generally best when it is felt rather than explained so that it is emotionally resonant. Exceptions are when both characters are scientists (see Primer).

The most emotionally evocative moment in the sequel is when McFly, after taking a spin in 2015, returns to his own time of 1984 and sees a veritable dystopia where his high school enemy (Biff) is now a ruler… who married his mother. That’s a visceral shock that requires no exposition.

Moments like those are the strength of big-budget time travel franchise films because they have a scale that allows characters to contend with possible dystopias firsthand, be they planets of apes or terminators, literalizing questions about the inevitability of fate and whether we can truly effect change.

TIME LOOP FILMS FROM 1990 - PRESENT

The best time loop film is and forever will be Groundhog Day (1993). The film teaches us that instead of being cynical, eroded by life’s repetitive nature, each day should be lived fully and with generosity.

The brilliant film revolves around a weatherman, Phil Connors (Bill Murray), who is eternally dissatisfied because he believes he is too good to work at his local news station. He lets this be known by making those around him miserable. When he is forced into what he considers a hell-on-earth job reporting on the world's “dullest” holiday, Murray is thrown into a time loop where he must repeat Groundhog Day over and over again.

What makes Groundhog Day so compelling and different from previous time travel films is that neither the film nor its characters are concerned with discovering why this time loop has ensnared Connors. There’s no alien DNA (Edge of Tomorrow), time machines (Primer), or magical hot tubs (Hot Tub Time Machine); Connors is only subjected to this time loop so he can grow as a character. What makes the film masterful is the delta from Connors’s selfish weatherman at the start to where he lands at the end: a legitimately selfless man who has gone through the heights of hell to change.

At the start of the film, Connors sees himself as the architect of his fate, declaring, “I make the weather.” Yet, as he finds himself caught in the time loop, this sense of agency disintegrates, morphing into despair masked by hedonism, “I don’t worry about anything anymore.” This leads him to view the universe as cruel and unchanging, stating, “It’s going to be cold, it’s going to be grey, and it’s going to last you the rest of your life.” Ultimately, he reaches a state of enlightenment, accepting his circumstances, declaring, “No matter what happens, tomorrow or the rest of my life, I’m happy now.”

The time loop serves as a metaphor for the human condition—how we often remain stuck in our habits, beliefs, and fears until we learn to appreciate the present. In surrendering control, he discovers that embracing the uncertainty of life and finds meaning in the present.

Most time loop films explore characters grappling with repetition in various contexts, from romantic relationships to war zones. Technically initiated by Claire Denis’ first short film, Le 15 Mai (1971), this time travel subgenre advanced the overall time travel genre by aligning it with how we all experience time. These films have deeper psychological concerns; they’re less interested in the external fate of the human race and more concerned about the internal feelings of the characters. Consequently, the term “Groundhog Day” has become a ubiquitous marker for the tedious nature of life.

Timecrimes (2007) is a time loop film about self-sabotage. Unlike many films in the genre, each loop is not a metaphor for life’s repetitive facets but an analogy for the protagonist’s moral decay, in this case, the destructive downward spiral of jealousy in a relationship.

The film centers on Hector, who has just moved into a new home with his wife. After becoming obsessed with a mysterious woman in the woods near his house, he is hunted by a bandaged killer who forces him to take refuge in a nearby research facility that houses a time machine. After being inadvertently sent back in time, Hector—now referred to as Hector 2—returns to his house, where he witnesses his earlier self (Hector 1) with his wife. Consumed by confusion and jealousy upon seeing his other self with his wife, he embarks on a crazed attempt to eliminate his earlier version.

The irony of his jealousy—which arises from seeing himself with his own wife—is that in trying to kill the other version of himself, he only ends up inflicting harm on himself. This self-perpetuating cycle highlights how jealousy can turn a person against themselves, illustrating the destructive consequences of mistrust in relationships.

It is a rare film featuring a time machine in which the main character is only concerned with the emotional ramifications, not technical explanations, of their time jump. When the time machine engineer—the scientist working at the nearby research facility— tries to comfort Hector 2, the film avoids the cliche of shifting Hector 2’s focus to what the engineer said, ruminating on lengthy, esoteric time travel descriptions (see Terminator 5, Back to the Future 2, and Deja Vu). Instead, the camera lingers on an inconsolable Hector 2. We soak up his sorrow and feel the emotional displacement of the time travel rather than the scene becoming overly scientific.

The film delivers a powerful conclusion as Hector 3, after yet another self-destructive loop, chooses to break free from his cycle of self-annihilation. He decides to move forward with his wife rather than remain trapped in the past. The film speaks to how self-sabotage and psychological obsession poison our relationships and pull us into emotionally destructive loops.

Edge of Tomorrow (2014) is a big-budget time loop war film that foregrounds cycles of hero creation. The film’s setting is the military-industrial complex, which rewards courageous martyrs who take control of their fate through self-sacrifice.

The film begins with a coward, Major William Cage (Tom Cruise), a military PR officer who has avoided military duty his entire career. But when he is forced into battle with no combat experience to fight an alien race called “Mimics,” he dies very quickly, but not before pulling a pin on a grenade and taking a massive alien with him to the grave.

His suicidal act, whether it be of self-preservation or a shimmer of self-sacrifice for his countrymen, initiates his journey from coward to hero. He gains the Groundhog Day-like ability to relive his day (the military twist here is this only happens once he dies), ensuring that with each successive death, he fears dying less and less until he sculpts himself into the perfect soldier. He becomes a man who knows his future ends in certain death and, through successive repetition, develops the iron will to save his species.

Further bolstering the film’s infatuation with the eternal value of heroes is the repeated image of Emily Blunt’s visage painted on buses and buildings. She is held in high regard because she is a soldier who killed hundreds of alien enemies on her first day of battle, becoming dubbed the “Angel of Verdun." Figuratively transcending her human form as an emblematic angel. Now, held up as a shining example of courage.

From a narrative perspective, the film gracefully moves through its time loops without becoming predictable, overly repetitive, or breaking its logical conceits—challenging to do in practice as there were 25+ time loop films produced between Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow.

Waking up alive after dying for the first time, Cage is remarkably confused, but at no point is this disorienting for the audience because they are aligned with his confusion. Serving as an audience surrogate, Cage gradually eases us into this world as he too uncovers the rules of his newfound inability to die. Note that these cycles of confusion and emotional clarity were perfected in Groundhog Day.

What elevates Edge of Tomorrow is that Cage is intrinsically linked to the film’s antagonist. Not only does Cage acquire the power of time travel from the film's aliens, but this ability becomes the sole means by which he can ultimately defeat them. This deep connection weaves a thread of dramatic irony throughout the film. In a twist, as Cruise masters his time loop and prepares for the climactic confrontation to kill the mother alien, Cruise loses his ability to wake up alive after dying. This forces him into the third act without the safety net of immortality, not only exponentially raising the stakes but also forcing him to ascend to the true definition of a courageous hero.

Palm Springs's (2020) time looping maps the hilarious evolution of living life debaucherously to the polar opposite doctrine. The film’s protagonist, Nyles (Andy Samberg), begins the film believing life is pointless, so why not make the best of it? Ultimately, he comes around to understanding that life is meaningful, inspiring him to treat others with kindness.

The film is well-studied in the mechanisms that made Groundhog Day successful. The Palm Springs filmmakers have boldly re-imagined that movie’s structure, starting their film at the first act turning point of Groundhog Day, when Connors dives into the corporeal pleasures of his time loop (smorgasbords and sex). In addition, ingeniously, Palm Springs introduces a second person into the time loop making it a deeper referendum on finding meaning in relationships.

Palm Springs opens at a high point. Nyles has lived the same wedding (not his) many multiples of times over and, like Connors at the end of Groundhog Day, seems to be excelling. Nyles crushes his wedding speech, so much so that nonagenarian June Squibb (Thelma) fawns that it was the best she’s heard in her lifetime. Nyles later sashays through the dance floor with such confidence that he can, in a single spin move, grab a guest’s drink, take a sip, and return it without them even noticing. He even woos the most depressed girl at the party, the bride’s sister Sarah (Cristin Milioti), who fails to make a wedding speech). So, later in the evening, it makes it pretty easy for Nyles to coast through watching his girlfriend cheat on him. He’s seen it, tried to stop it, and is now over it.

As opposed to other time loop movies, the film's inciting incident is not Nyles getting stuck in a time loop because he’s already there, but instead, a new character getting stuck for the first time with him. As Nyles says, "It's one of those infinite time loop situations you might have heard about." That’s what he tries to tell Sarah, who unexpectedly enters a nearby cave, the portal to becoming stuck in the time loop of this Palm Springs wedding. As Sarah reckons with her fate, navigating every escape route from trying to stay awake as long as possible to suicide, Nyles is the only one to turn to because his approach to dealing with the loop has been cemented… or so he thinks.

In contrast to Sarah’s initial panic, Nyles appears self-actualized, embracing a form of enlightened nihilism: since everything is ultimately meaningless, why not just enjoy the moment? By having Nyles approach the situation with a carefree outlook, the film sidesteps lengthy, unnecessary explanations of the mechanisms of the time loop, shifting the focus to character development rather than the mechanics of time travel.

One of the film’s strengths is that the time loop allows the characters to rise above cynicism in the face of life’s repetitive facets, preventing them from falling into negative cycles of psychological self-destruction.

But in the third act, the film fumbles.

Sarah abandons Nyles to learn quantum physics so she can run experiments on how to blow up the cave and thus the time loop. That storyline is overly plotty and feels outside the scope of the terms the movie sets up because the film has moved from having the characters solve their problems emotionally to technically.

The prime issue with films having a time machine/time portal is that it creates a structural burden to interface with a time machine, which can feel conceited if the characters are not scientists.

In the penultimate scene, Sarah corrects her mistake at the start of the film by giving the perfect wedding speech to her sister. But, her character development, from being self-centered to selfless, feels predicated entirely on her belief that she will escape her time loop.

Contrast this with Connors’ final loop in Groundhog Day, where he exhibits unconditional generosity despite not knowing he’s about to break out of his cycle and wake up in a new tomorrow. Many post-Groundhog Day time loop films with a romantic element have struggled with similar faulty character growth.

The time travel rom-com Meet Cute (2022) uses a different time loop setting: a first date. While it utilizes some time travel conventions well, it is ultimately undermined by the genre's pitfalls.

The film’s opening scene, in which Gary (Pete Davidson) and Sheila (Kate Cuoco) meet in a bar for what seems to be the first time, confidently employs two conditions that arise for characters struck in time loop films. The first is the decay of the human spirit through repetition. This becomes apparent when Sheila’s eyes subtly drift as Gary opens up about his childhood trauma because, well, she's actually been on this date many times before and heard that story a hundred times. The repetition catalyzes her disconnect from reality, eroding her ability to engage meaningfully with Gary in his vulnerable moments.

The second lesson is learning from your loops. When Gary panics after spilling his beer on someone, Sheila knows exactly what to say to comfort him, “It’s okay for things to be messy sometimes.” And it works like magic: Gary’s panic subsides. The film suggests that knowing how to help a partner break their negative patterns is the kind of relationship dynamics refinement, found only through repetition, that is valuable.

But after the well-constructed opening, Meet Cute derails. While Connors is perpetually stuck in Groundhog Day by an unknown force, Sheila actively chooses each day to return to her time machine to go back to that first date. She is not externally stuck, which weakens the film's credibility in so far as Sheila is not actually trapped on a first date. The entire logical framework of the film collapses because she has an easy out: to move forward with her life or time travel to a different day.

Meet Cute mishandles a key genre convention: the use of flashbacks. In a time travel film, flashbacks can undermine the narrative's clarity. These temporal jumps often feel overly expositional rather than being motivated by the characters’ circumstances. When the protagonist possesses a time machine capable of taking them to any point in time, flashbacks are redundantly unnecessary and can disrupt the forward momentum of the story.

Time loop films are most resonant when the protagonists become less selfish, like in Groundhog Day, Edge of Tomorrow, and Happy Death Day (a Blumhouse horror film that transitions a snarky sorority sister to a loving girlfriend through her getting murdered eleven times). They resonate because, to some degree, we can all feel like our lives are filled with endless repetitions. These films teach us to break out of our negative, destructive loops, whether externally or internally imposed.

FRACTURED EXPERIENCES IN HUMAN TIME FROM THE 60s - PRESENT

La Jetée (1962) is a thirty-minute time travel masterpiece told entirely in still photos. The film bridges the gap between mental time travel and physical time travel better than any other film in the “fractured experiences in human time” subgenre.

The film takes us into the mind of a man traumatized by his past who is forced to travel to both the past and the future to save all of humanity. The film opens during the man’s boyhood when he witnesses the horrific killing of a man on a pier. Later, World War 3 reduces society to rubble, and he flees underground, along with other survivors who devise time travel experiments to save themselves.

A voiceover (translated into English) explains:

“The way that the human race was doomed, space was off limits. The only link with survival passed through time, a loophole in time and then maybe it would be possible to reach food, medicine, energy. This was the purpose of the experiment, to throw emissaries into time, to call past and future to the rescue of the present.”

The main character's childhood trauma of witnessing the death on the pier opens up a mental channel into the past. His trauma connects him to the past and the future, which metaphorically links the time travel on screen to therapy. According to the film, when one’s present is psychologically “doomed,” as is the human race in La Jetée, there are only two solutions. One is mental time travel to the past, calling on memories to decode the source of our suffering, a sort of mental “medicine.” The second is imagining an optimistic future to gain mental “energy.” Like the doomed human race in the film, we can draw on the past and the future in our lives as a source of renewal.

La Jetée further bridges literal and metaphorical time travel through its poetic lyrical style: the film conveys a first-person sense of the protagonist’s disorientation as he undergoes repeated trips to the past where he meets a woman. As he travels back in time to see her, a voiceover comments:

“He never knows whether he moves towards her. Whether he is driven, whether he has made it up, or whether he is only dreaming.”

Their relationship is portrayed as a series of fleeting moments, them exploring a museum and walking in a park; it’s a fractured relationship, where he dips in and out of her physical world. Physical, like mental time travel, pulls one out of the present, threatening to destroy relationships. In the film, this condition prevents him from being fully present with her.

At the end of the film, the voiceover concludes:

“He looked for a woman's face at the end of the pier. He ran towards her, and when he recognized the man who had trailed him… he knew there was no way out of time. And he knew that this haunted moment he had been granted to see as a child was the moment of his own death.”

This ending masterfully renders the opening death on the pier as a paradox. It’s astounding because of the clarity by which it cuts to the core of collective fears of death. There is no escaping our demise, similar to Cage’s time loop in Edge of Tomorrow, but much more pessimistic in that it shows that the human condition is that of living in perpetual fear of a future we know is guaranteed to end our lives.

La Jetée’s use of still photos further adds to the fractured way we experience memories: glimpses of images strung together. It is a radical departure from any film before or after, even its own adaptation into 12 Monkeys (1995).

Alain Resnais’ Je t’aime je t’aime (1968) suffers from one of the prime prevalent problems in the fractured psychological time travel film: the protagonist rarely reckons with his unique circumstances.

The action centers around Claude Ridder (Claude Rich), a suicide survivor. Upon being released from the hospital, Ridder is captured by a secret group of scientists experimenting with time travel. He is prepped to go into the past for one minute, but the experiment fails, and he ends up ping-ponging around his past, sometimes repeating the same moment but more often traveling across an array of memories. Through all this, he is a passive observer. While reliving his past, he is never aware that he is time traveling. He is never present in his past. These moments function more like flashbacks because he has no autonomy within them.

Only once in the film does he return to the present and “wake up” from his constant bouncing around. He then proceeds to describe what’s happening to himself inside the time machine. But, it’s a very short self-reflection.

Contrast this with Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), who comes awake as he travels through his memories and thus is active in driving the narrative because he has a core purpose (to hold onto his memories).

Another non-time travel film that deals with how memory shatters our sense of time is Memento (2000). In this film, the lead, Guy Pierce, constantly reacts to his specific temporal, fractured condition. Without these reflections, the audience can’t connect their psychological experience of memory to what they see on screen.

As Ridder states in a rare moment of self-reflexivity in Je t’aime je t’aime, his life is frustratingly static, “It's 3 pm, 3 hours to go, 3 minutes ago it was 3 pm, in 3 weeks it will be 3 pm, in a century too, time passes for everybody. But me, it stays static. It's 3 pm forever.” The film would have functioned better if it was a similar length to La Jetée because the arch of the film is intriguing: Je t’aime je t’aime is not a movie about a suicidal time traveler reckoning with his depression but about him coming to terms with his guilt for killing his girlfriend of seven years. Time travel as a mechanism for guilt stacks with the character’s experience of reliving his memories, but a lengthy section in the middle interrupts this connection, making it harder to fully grasp the emotional weight of the narrative.

The director, Alain Resnais, is more successful in exploring fractured temporal human experience outside of the science fiction genre in Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad (1961).

The marvelously crafted Slaughterhouse-Five (1972), an adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s book of the same name, is a grand lesson in becoming disconnected from time in a way that helps us live more fully. This film is the thematic opposite of La Jetée, which examines this idea in a negative light. In Slaughterhouse-Five, the central character, Billy Pilgrim (Michael Sacks), becomes “unstuck in time.” This condition at first leads to crippling disorientation, analogous to post-traumatic stress disorder, but ultimately teaches him to accept death as a part of his life.

Much of Slaughterhouse-Five’s action centers on Pilgram ping-ponging from fighting in World War 2 to his postwar marriage and back again in meticulously edited sequences. These include a photo being taken of Pilgram during the war, which ricochets him to his wedding years later, where pictures are being taken. Later, bombs dropped on Dresden cut with the red flashes of traffic lights in New York. In another scene, German war camp showers match cut to him bathing as a boy.

Towards the end of the film, Billy gets stuck on the planet Tralfamadore in a human zoo with a woman who muses, “You time-tripping again? I can always tell you know, when you've been time-tripping. You're back in the war, weren’t you? Time travel is a bitch for you, isn’t it? Particularly the war.” As this woman is seducing Pilgram, he asks for a kiss but is thrust back into his past, hiding in a WW2 bunker where his fellow soldiers overhear his request for a smooch and berate him for being a homosexual.

His continual disorientation of getting thrown from present to past leaves him hazy-eyed and aloof. That’s what makes Pilgram’s time travel feel like trauma: the pain of his personal past disconnects him from being alive in his present. The film is able to feel grounded because Pilgram’s awareness of his unique circumstances is analogous to post-traumatic stress disorder.

As Pilgram hits a low point in his life, bedridden by the emotional pain of constant time jumping, he is abducted by aliens (Trifadors) who live in the 4th dimension, unbounded from time. They imbue Pilgram with a philosophy that allows him to see the beauty of his condition, stating: “A pleasant way to spend eternity is to ignore the bad times and concentrate on the good.” From this, Pilgram learns to accept that he is one day going to die. In fact, he’s seen his moment of death during a speech he gives at a university. Moments before his demise, he states: “Many years ago a certain man promised to have me killed. He's an old man now. Living not far from here… He's insane, but tonight he'll keep his promise.” The crowd rises into a panic, and Pilgram parries back: “If you protest, if you think that death is a terrible thing, then you've not understood what I've said. You see, it's time for you to go home to your wives and your children. It's time for me to be dead…”

Pilgrim, being unbounded in time, knows the moment that he's going to die. Thus, he is able to embrace the notion of being unstuck in time, where he has a sublime disconnectedness that allows him to embrace and live in each moment presently.

The grand takeaway from the film is that we, like Pilgrim, might not know when we are going to die but we know that we will and that should double us back into life and make each moment more resonant.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983) examines the disorienting high school experience of falling in love. By intertwining the supernatural with everyday life, the film delves into how love can alter our perception of time, reality, and self-identity. The film was a major success in Japan, sparking an anime adaptation in 2006 and another live-action film in 2010.

The film opens with a striking quote: “When one discovers love that transcends reality… is that fortunate or not.”

The film centers on high school girl Kazuko Yoshiyama's (Tomoyo Harada) accidental exposure to strange lavender-scented steam in her science lab, which triggers her to time-leap. At first, she experiences brief temporal fluttering, like watching a bike rider jump a few feet past her (skipping the distance between), or time looping, like a single arrow she shoots at a target, striking it multiple times. Later, her condition becomes more severe. After an earthquake, she experiences the same high school day again and freaks out all her classmates. However, she finds a confidant in her childhood crush, Fukamachi. When she realizes she’s in love with him but can’t express it, she bounces back to a tender childhood memory they shared.

The film deals with the disorientation of falling in love. How do you recognize romantic love for the first time? How do these feelings manifest? How do we express them?

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time succeeds by having Kazuko be 100% lucid and aware of her condition and actively trying to seek guidance to reckon with it, allowing us to become sucked in by her predicament. The film portrays love as a force that transcends time and logic.

Primer (2004) is a time travel masterpiece made for $7000. The beauty of the film is that while much is complex, from the scientific jargon to the characters’ increasingly convoluted time jumps, we are never not clear on what is going on. That’s because we are always provided a simple thing to latch on to.

The first ten minutes of the film are filled with heavy startup jargon, the characters working away in their garage to be the next Steve Jobs, ripping machine parts from their car—what they’re building is not clear. But the VO synthesizes the on-screen action and points us to what is important: “They took from their surroundings what was needed and made of it something more.” These contrasting formal choices marry the viewer to the hyper-realism of the science on screen, priming us to buy into the impossible.

Before the big reveal that the scientists have constructed a time travel device, we’re baby-stepped into a slightly more probable notion: they’ve created a machine to reduce the weight of objects.

When they turn this machine on, Aaron (played by Shane Carruth, who also wrote and directed the film) disconnects the power source, two 12 V batteries. But the machine is still on. We can hear it whirring. Again, the complexity of trying to understand applications for a weight reduction device is paired with a gross simplification: a machine can’t run if it’s off.

And that’s where Primer continues to excel. Most time travel films will instantly jump into esoteric descriptions of time machines or paradoxes (see T5) that leave the viewer disconnected from the action. Primer waits a full 30 minutes (nearly 40% of the way through the film's razor-thin 77-minute runtime) before we see any time traveling occur.

Primer also baby steps one of the keystones of a time travel movie: the visceral negative consequences the time traveler endures for using the machine. While most in the genre are overly hyperbolic, offering lengthy or didactic exposition about the possible end of the world or death via the grandfather paradox, Primer keeps things localized to our main character’s experience. Minor physical symptoms manifest:

Bloody ear

Bad handwriting

These prime us for the larger dangers. By the third act, we are so tightly locked into the character’s perspective that when the on-screen action enters a higher level of complexity, as the characters start crisscrossing time in multiple time machines, killing themselves in the past to prevent their doubles from occupying their present, we are swept up in the disorientation as a function of their experience of time. This is similar to the shared audience/protagonist disorientation in Edge of Tomorrow.

The disorientation that characters undergo on screen as they try to keep track of their time traveling is in lockstep with the audience’s experience of the film. We also lose track of time in the same way, which ratchets us closer to the characters' experiences.

The oddity of this film is that the more one watches it, the more one understands what is happening, which causes a misalignment between the viewing experience and the main character’s confusion.

But through and through, the construction and the looping in Primer are well-diagrammed and ingenious.

Déjà Vu (2006) traps itself by introducing a time travel device that is passive. It is a rare film that is set up with the rule that the characters can only use the device to view the past like a TV screen, hearkening back to The Ghosts of Slumber Mountain.

Déjà Vu opens with the horrific bombing of a ferry, killing 500+ people, a crime that Doug Carlin (Denzel Washington) tries to solve by using a device that can see exactly four days and six hours into the past. The device is described as a window into: “A single trailing moment in the past.” If the filmmakers had explored every angle of this concept, much of the film’s absurd logic could have been avoided.

Instead, to justify Déjà Vu as a Denzel Washington action vehicle, the filmmakers create a series of rules that are broken by increasingly ridiculous action sequences. The first rule is that the range of the time travel device is geographically limited. This is dismissed almost instantly by a ridiculous action set piece. Carlin drives around downtown New Orleans with range-extending goggles that allow him to see into the past (a la The Ghost of Slumber Mountain). The second rule that is very quickly broken is that no person can be sent back in time. Later in the film, Washington travels back in time, so he can have a shootout with the terrorist.

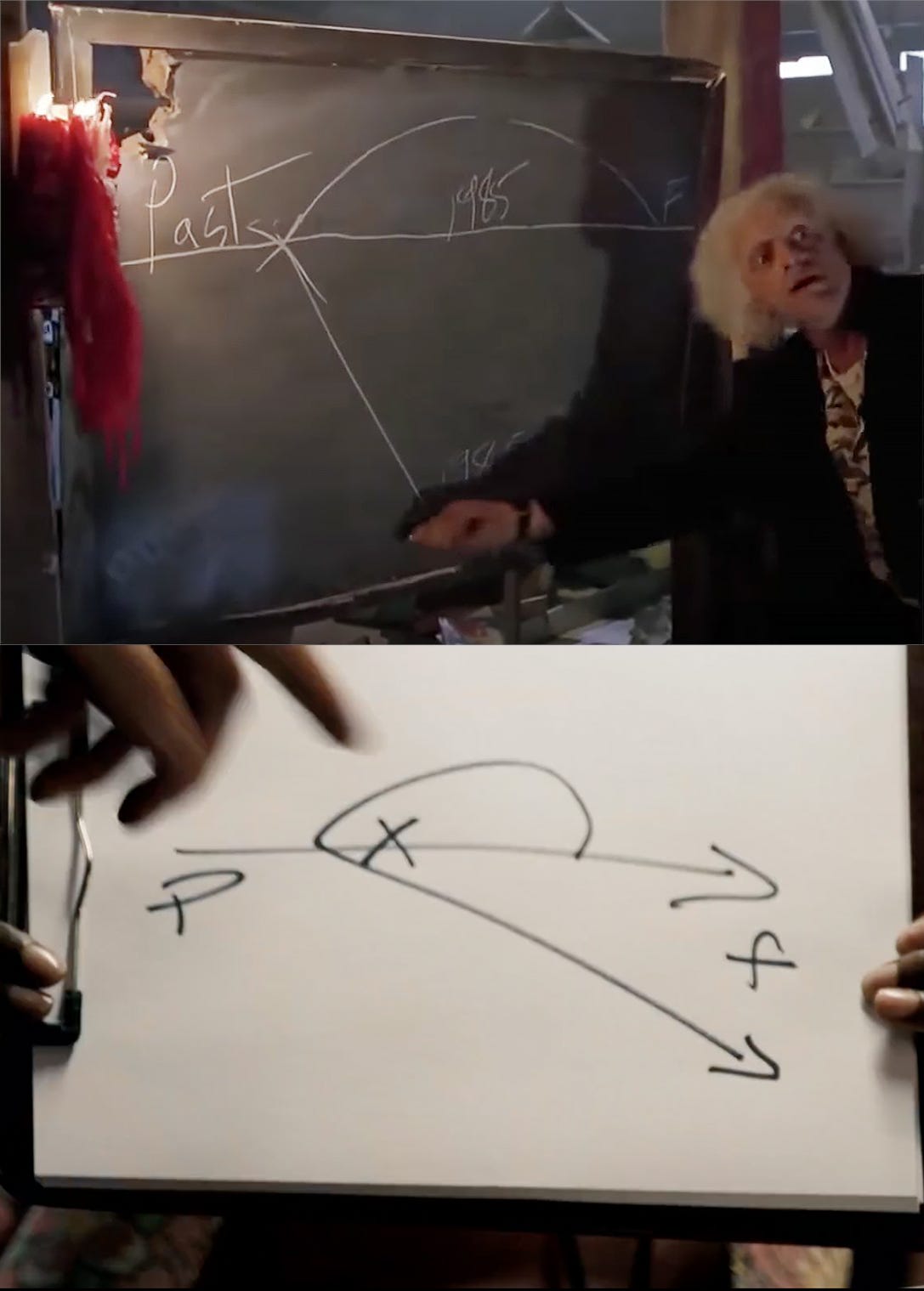

Much of the time travel logic is a copy from previous films. Compare how the time travel diagram Carlin sketches is virtually identical to Dr. Emmett Brown’s in Back to the Future Part 2:

Above all else, Déjà Vu makes the cardinal mistake of disposing with logic while taking itself too seriously.

Looper (2012) is incredible at centering on how to stop cycles of self-destruction. What is most profound in the film is the idea of empowering each of us to change our fate by taking action in the present.

In the film, the final job of every “looper” is to kill an older version of themselves (sent from the future to the past). While the film opens by painting this as a metaphor for negative decisions in the present destroying our future, the end of the film flips this notion with Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) ending his destructive cycles of violence by killing himself.

The film continually lays out bad versions of the characters’ futures. Here’s crime boss Abe (Jeff Daniels) talking to his employee Joe, “I could see it happening on the TV, the bad version of your life like a vision, I could see how you turned bad so I changed it. I cleaned you up and put a gun in your hand.” At the end of the film, Joe sees everyone’s future: “I saw a mom who would die for her son, a man who would kill for his wife, a boy angry and alone, laid out in front of him with a bad path. I saw it. And the path was a circle, round and round. So I changed it.”

Each scene foregrounds negative or positive outcomes of the characters’ futures to show how forethought allows us to take control of our destiny.

From a script point of view, Looper is very good at actively resisting the time travel trope of explaining heady logic. Here’s Abe: “This time travel shit just fries your brain like an egg.” And later, Bruce Willis (who plays an older version of Gordon-Levitt’s Joe): “I don’t want to talk about time travel shit, because if we start talking about it then we’re going to be here all day talking about it making diagrams with straws.”

Structurally, Looper also succeeds in having a linear narrative only interrupted by a single flashforward montage of Joe (Gordon-Levitt) aging 30 years into Willis before looping us back to the present. It’s technically a flashback for Willis and lasts less than 6 minutes, so it never interrupts the narrative flow—we get the required information and bounce back to the action of the present, much like how the flashforwards function in Terminator 1 and 2.

Ultimately, Looper uses the mechanics of time travel not merely as a flashy sci-fi device but as a profound metaphor for the cycles of behavior that destroy or define our lives. By confronting the destructive patterns that ensnare its characters, the film delves deep into themes of free will, self-sacrifice, and redemption. Joe’s decisive action to end his own life—to prevent a future marred by violence and suffering—embodies the empowering notion that we can alter our destinies by the courageous choices we make in the present.

Tenet (2020) fails because director Christopher Nolan makes the cardinal mistake of becoming overly detailed with complicated dialogue, action sequences, and, ultimately, logic.

Take the climax, which features:

Three armies

1 moving forward in time

1 moving backward in time

1 enemy trying to blow up the world

Parallel yacht sequence

Husband trying to kill himself to destroy the world

Wife trying to stop him, but ends up killing him instead

Wife’s double

This is indicative of the layers of complication throughout Tenet, which prevent us from getting a clear perspective of what to care about.

Robert Pattinson's parody of the final dialogue from Casablanca at the end of the film adds a great relationship element to the film. However, time travel movies that do not offer insights into the human experience of time struggle to establish a meaningful connection with viewers. As such, this is the most poorly received film of Nolan’s career.

Like Alain Resnais, Nolan is more successful in exploring fractured temporal humans experience outside of the time travel genre in Memento (2000) and Inception (2010). However, there is a beautiful reckoning of the effects of time dilation in Interstellar (2014) when Matthew McConaughey watches decades’ worth of messages that his daughter sent, which for him has passed by in a matter of minutes, causing McConaughey to lose it (clip).

This subgenre, above all the others, links mental and physical time travel and succeeds when the on-screen action doesn’t cannibalize our deeper understanding of how we reckon with the experience of being creatures that live physically in the present while also being able to mentally time travel to the past and the future.

CHAOS THEORY IN TIME TRAVEL FILMS

Of all the action-packed time travel films that have been made Run Lola Run (1998) is the most engagingly energetic time travel film* of all time. It is obsessed with time— not only the ticking clock that throttles the action to a breakneck pace but also how variations in timing can alter the very fabric of our existence. It is a film about chaos theory that also allows us to consider how randomness determines our romantic destiny.

Run Lola Run is an adrenaline shot straight to the arm, built off the battery acid of German techno music, the kinetic energy of Lola (Franka Potente), and rapidly paced time loops. The film opens with Lola’s boyfriend Manni in desperate straights: he’s lost 100K German Marks (≈ $87K) and has twenty minutes to get it back before being killed. He phones Lola, who tells him she’ll come up with the money in twenty minutes—she’s just not sure how.

From there, every frame of the film is fueled by chaos theory, which states that complex systems are very sensitive to minor changes in conditions and that small alterations give rise to wildly different consequences.

The film is structured with three back-to-back attempts of Lola trying to get the money. These function as 20-minute time loop short films with a simplified three-act structure. They vary in every detail but share the same inciting incident: Manni’s phone call for the money.

As Lola sprints through Berlin, trying to come up with the cash in various permutations, she bumps into a trio of people, and we learn their fate through a series of rapid-fire photographs (which change when she bumps into them in each subsequent time loop):

Pedestrian 1: A middle-aged lady with a baby

Fate 1: child services takes her baby, so she nabs a kid from a park

Fate 2: wins the jackpot

Fate 3: becomes a religious woman

Pedestrian 2: Guy on bike

Fate 1: A bike accident leads him to fall in love with the woman who helps him recover

Fate 2: heroin overdose

Pedestrian 3: Bank worker

Fate 1: Gets in an accident, reducing her to a wheelchair, and kills herself

Fate 2: meets a young banker who becomes her kinky sex toy

Run Lola Run is obsessed with how randomness is the prime decider of our relationships. It displays the condition that we have no control over our lives and are beholden to the universe’s whims. Lola’s character shares these concerns, at one point opening up to Manni, “What if I was some other girl… what if you never met me.” Lola is deeply disturbed by the unpredictable nature of her life, a feeling that leaves her momentarily discontent with her relationship, which she feels is meaningless.

In the film's first two time loops, chaos theory is depicted negatively, implying that the universe’s randomness is tilted against us, inevitably leading to poor outcomes—a judgment so severe it borders on nihilism. However, the final loop subtly shifts this perspective, suggesting that sheer willpower can shape fate, as both Lola and Manni successfully acquire the money. Thus, randomness isn't just a marker of misfortune; it can also be a catalyst that empowers us to seize control of our lives.

In this time travel film, chaos theory is predicated around two prime building blocks of the universe: cause and effect. The linkage of the two is an important metaphor for how our intertwined reliance on our romantic partners shapes our shared destiny. When the universe lines up, and we find our soulmate, there is an imperative to be blissful, knowing we’ve bested chance.

*Although Run Lola Run is not strictly a time travel film because it is time-obsessed and features three different versions of the same event, where Lola seems to learn from each loop, it shares more than enough DNA to warrant inclusion.

The Butterfly Effect (2004) is a time travel movie that loses its potency because the protagonist is painfully myopic. It sensationalizes chaos theory to the detriment of the viewing experience (unlike the successful Run Lola Run).

In the film, Evan Treborn (Ashton Kutcher) suffers blackouts during traumatic events in his life. As he grows up, he finds a way to access these lost memories by reading his journal, which allows him to time travel to his frightening childhood traumas:

His lunatic dad strangling him

A neighbor filming him in kiddie porn

His childhood friend setting his dog on fire

When Treborn travels to these moments in his past, he changes them, which alters his future in a way that leaves him consistently unhappy. Thus, he keeps returning to the past to fix these mistakes. While Run Lola Run explores the unpredictability of fate with vibrant energy, The Butterfly Effect devolves into repetitive attempts by Treborn to fix his traumatic past. Treborn's continual belief that he will have a better future if he changes his past gets stale. There’s no character growth, and for that reason, the film becomes exhausting.

Where Run Lola Run employs chaos theory as a means of contemplating the highs and lows of how randomness influences love, The Butterfly Effect uses it primarily for shock value, as when Treborn wakes up in the present with no arms after changing the past.

The midpoint, delivered by Treborn’s destitute friend, serves as self-reflective feedback, which the filmmakers overlooked: “Is there a point to any of this?”

Interestingly, the film ends on an identical character beat as Looper (2012), which the latter is able to execute with greater sophistication and deeper meaning.

The challenge for time travel films in this sub sub genre is trying to make meaning out of randomness. And using that randomness as an effective mechanism for meaningful change.

TIME TRAVEL ROMANCE

There is a subset of romance films that feature time travelers that work well by playing on our deep nostalgia for the past—such as Kate & Leopold (2001), in which Hugh Jackman plays a 19th-century Duke who goes through a time portal and meets Meg Ryan circa 2001, who enjoys his 19th-century whit.

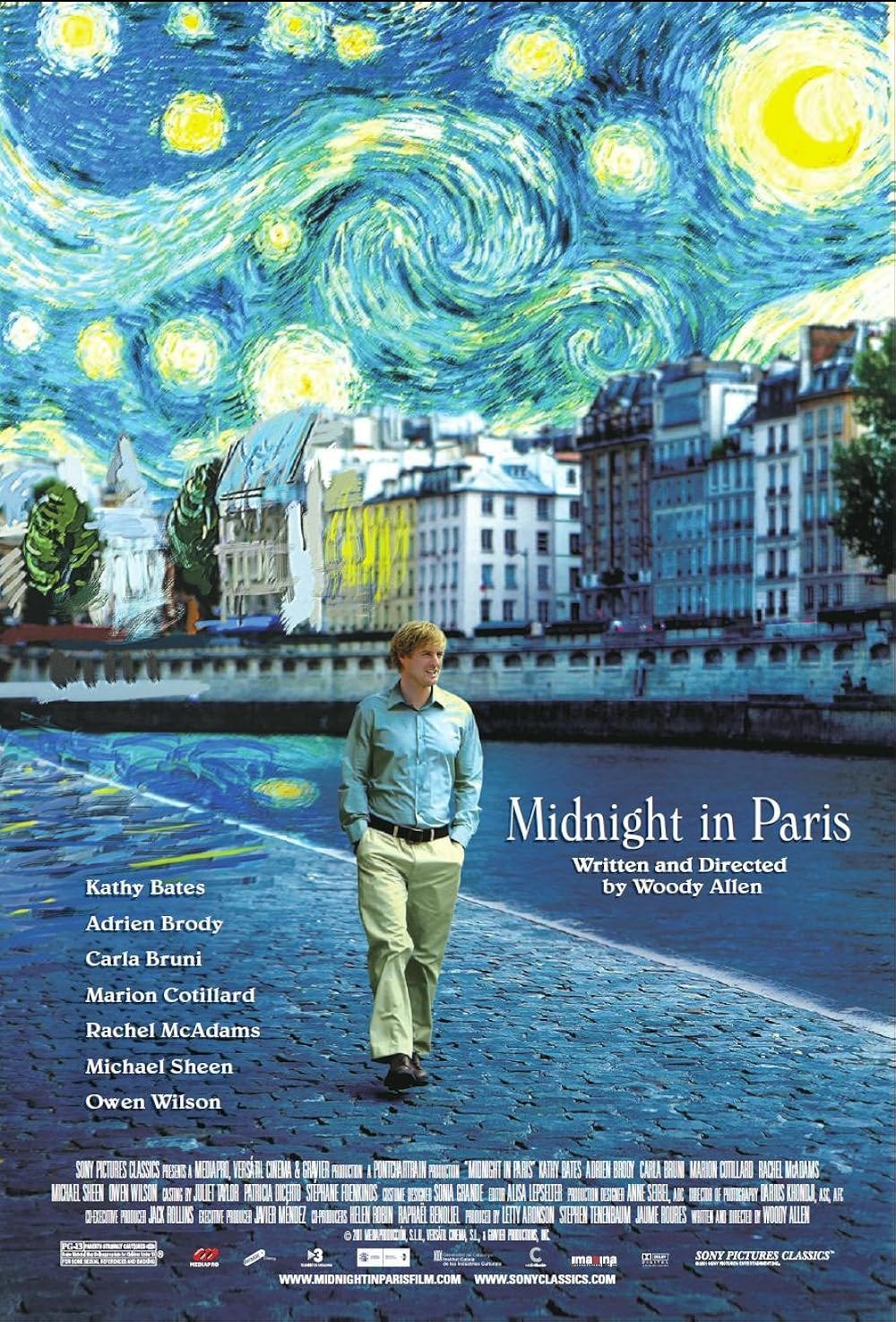

And of course, there’s Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris (2011), the first travel film to earn a nomination for Best Picture, where Gil (Owen Wilson) pines away for the golden era of Parisian artists… and meets them firsthand on his midnight strolls only to discover that those 20th-century greats are also pining away for the previous generation. This charming film ultimately points us back to living in the present.

More often than not, though, time travel romance films leave something to be desired:

In Somewhere in Time (1980), Richard Collier (Superman’s Christopher Reeves) becomes obsessed with a 70-year-old photograph. He consults an old professor about time traveling to her and then quasi-meditates in his bedroom, removing all modern objects and getting bolted to the past. The film is overdone because of painfully belabored exposition.

In Lake House (2006), Kate Forster (Sandra Bullock) and Alex Wyler (Keanu Reeves) make the most important discovery in human history: a time travel device embedded in a mailbox that connects the years 2004 to 2006. Instead of trading lottery numbers or warning the government about Hurricane Katrina (which happened in 2005), they use it to be pen pals.

The entire plot is built around Forster (who lives in 2006) and Wyler (who lives in 2004) being too skittish to meet in their present despite living in the same city. We’re told they fall in love, although this is incredibly hard to buy into. At neither point does either character just look the other one up in their present, even after they meet accidentally at a party.

In The Time Traveler's Wife (2009), Henry (Eric Bana) possesses a unique gene that forces him to time travel involuntarily. This seeming randomness of his time travel makes the film feel engineered. For example, Henry always seems to time travel during significant moments, therefore missing them. When he time travels right before he takes the alter on his wedding day, it feels contrived.

But the worst quality of the film is that it gets stuck contending with the physical challenges of Henry’s time travel, e,g. him having to find clothing when he shows up in the past naked (a la Terminator) or later seeking a gene therapist to check his “Chrono gene” instead of contending with the emotional challenges that his unique condition presents.

The film teases three possible emotional circumstances that could be resonant but never commits to them.

The first is Clare (Rachel McAdams, the time traveler’s wife), who seems most infatuated with the older version of Henry, who is more mature. If the film tilted this direction, it could have interrogated our desire for our partners to mature.

The second is Clare is occasionally upset when Henry misses important moments in their lives, like Christmas and New Year, but only once in the entire film does she confront him about being an absent partner.

Thirdly, the film starts with Henry declaring that his time travel condition is linked to events in his life with larger emotional gravity. Still, we only see him contend with this a single time when he visits his mother before she dies. The film misses the opportunity to paint Henry’s condition as analogous to our mental time travel when we obsess over past traumas.

The recent The Greatest Hits (2024) had a unique concept: a girl whose boyfriend passed away gets catapulted in time before his death whenever a song they listened to together plays on the radio. But it gets bogged down with a character that continually refuses to move forward.

The best time travel romance film made to date is About Time (2013).

The film imbues all the men from a certain family with the ability to time travel to their past whenever they choose. But crucially, these Godlike powers are used for petty purposes, as when Tim (Domhnall Gleeson) tells his father (Bill Nighy) that he will use his time travel ability to solve the biggest problem in his life: finding a girlfriend.

Therefore, the film doesn’t try to contend with more significant questions about destiny but instead is a referendum on living well with the time we’re given.

As such, the best part of About Time is when Tim resists using his superpowers, like when he doesn’t sleep with his first love (Margot Robbie) and instead asks for his girlfriend’s hand in marriage. Later, Tim muses, “Time travel seems almost unnecessary because every detail of life seems so wonderful.” At the very end, his time traveler lesson becomes universal: “We’re all traveling through time together. Every day of our lives. All we can do is do our best. To relish this remarkable ride.”

That’s my favorite kind of time travel film, one that argues that we’re already living our best lives.

The genre is filled with some of the most emotionally evocative moments in cinema history, like when the captain in the first Planet of the Apes sees the Statue of Liberty blown to smithereens and realizes that he’s not in the past but in the future, connecting all periods in time through the horror of human violence.

My favorite moment in a time travel film is at the end of Groundhog Day, when Connors wakes up in a new day, the day after Groundhog Day. With joyous euphoria, he exclaims, “You know what today is? Tomorrow.” This suggests that each new day we experience is an act of time travel into the future, where we are already actualized as the best versions of our future selves. It is the most beautiful realignment of a time perspective.

"Somewhere in time" deserves more than a mere mention. It really put romantic time slip films on the map and created its own genre.