*Disclaimer

I’m David Larkin, former Head of Business at Letterboxd.com and Founder of GoWatchIt. I never worked for Netflix. I’ve only done a little business with them on the marketing side. Everything in this piece is stitched together from public information. So if anyone at Netflix thinks I’m wrong about any of this, they’re almost certainly right.

Netflix is the most successful company in Hollywood in terms of profit margin and global scale — it reaches more paying viewers and generates more film and TV revenue than any studio in history.

This dominance was built on over two decades of unbroken annual revenue growth. But none of this was ordained.

Between 2017 and 2019, many analysts openly questioned whether Netflix’s debt-fueled business model could survive. The company was burning over $3 billion a year in cash and issuing billions more in junk-rated bonds to fund its global expansion, prompting warnings from Wall Street that it was “addicted to debt.” Critics argued that a streaming-only model couldn’t justify such losses, especially as established rivals like Disney, WarnerMedia, and NBCU were preparing to launch their own competing platforms.

On April 19, 2022, Netflix announced the loss of 200,000 subscribers—its first loss in a decade. Netflix’s stock sank more than 20% in after-hours trading, and the stock officially fell by approximately 35% when trading resumed on April 20th. Netflix’s stock was already down more than 40% year-to-date, in large part due to increased competition and slowed user growth forecasts from Netflix for Q1.

But then they turned it around.

It wasn’t content that turned things around for Netflix, or even international expansion. It was software.

In the shareholder letter that immediately followed the subscriber loss announcement, Netflix revealed that in addition to its 222 million paying households, it estimated the service was being shared with over 100 million additional households worldwide, including a massive 30 million in the lucrative US and Canada market.

This wasn’t a footnote; it was the entire justification for an immediate, strategic pivot. The company explicitly stated its new focus would be to “monetize sharing,” effectively telling the market its biggest problem wasn’t content or competition, but a vast, untapped pool of over 100 million loyal viewers who simply needed to be converted into paying customers.

This moment marked the official end of the “love is sharing a password” era—a quote once attributed to former CEO Reed Hastings himself—and the dawn of Netflix’s systems-first strategy.

Netflix’s biggest hit wasn’t Stranger Things — it was killing password sharing.

What looked like a simple policy was actually a product: a system-level update that proved Netflix’s real advantage isn’t content, it’s system design. Years of internal testing and account-usage telemetry informed the rollout, allowing Netflix to convert millions of shared-account users into paying subscribers with remarkable precision — and only brief backlash.

In 2025, Netflix remains the clear global leader in streaming:

310M subs – Netflix

200-240M subs – Amazon

124-158M subs Disney+

117M subs Max (formerly HBO Max)

Together, these figures show that although competitors have narrowed the gap, Netflix still operates at a significantly larger global scale — a position that underpins its pricing power, advertising ambitions, and ongoing shift from subscriber growth to profitability and platform efficiency.

The key to understanding Netflix’s dominance is to shift focus: its success is not defined by the content lens relied upon by Hollywood, but by its core systems and product architecture. Netflix is a master at streaming operations and leveraging its global scale. Since much of Hollywood is playing catch-up, I think it’s useful to look at what exactly they need to catch up with.

The gap is visible in the numbers.

In Q3 2025, Netflix generated $3.25 billion in operating profit on $11.51 billion in revenue, translating to an operating margin of 28.2% across its approx 310 million subscribers — or roughly $10.23 of operating profit per subscriber per quarter.

By contrast, Disney’s streaming division (Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+) posted about $346 million in operating profit on 183 million subscribers in the same quarter—translating to nearly $1.89 per subscriber per quarter, or about one-fifth the profit per user of Netflix. Warner Bros. Discovery’s Max has achieved modest profitability but still operates at mid-single-digit margins, and thus significantly below Netflix’s per-user economics.

Taken together, the data reveals how far ahead Netflix remains — not only in scale but in profitability. Its margins approach those of a mature software business, while rivals are still working to reach sustainable per-user economics within legacy cost structures.

Realizing They Had a Problem.

When Stranger Things Season 4 premiered in May–July 2022, its record viewership helped stabilize engagement after Netflix’s first subscriber loss. The show set historic viewership records but, critically, Netflix still lost 970,000 subscribers in Q2 2022 — its second straight quarterly drop. The decline reflected a convergence of structural and competitive pressures: a post-pandemic correction following the record sign-ups of 2020–21; a content lull between major releases like Bridgerton and Stranger Things; and price increases in key markets that drove churn among mature, saturated households. At the same time, intensifying competition from Disney+, HBO Max, and others fragmented audiences, while Netflix still lacked both an ad-supported tier and a paid-sharing program to monetize non-subscribers.

Analysts estimate Stranger Things was responsible for driving 1–2 million incremental sign-ups across both quarters — respectable but temporary. Its direct subscription revenue impact, estimated at $100–150 million, was only a fraction of the show’s $270 million production cost. The financial lesson was clear: Even Netflix’s biggest hit could only stabilize the ship; it took a systemic, permanent policy like the password crackdown to generate billions in durable, high-margin revenue.

This insight coincided with Greg Peters becoming co-CEO in January 2023.

Peters had previously served as Chief Operating Officer (COO) and Chief Product Officer (CPO) at Netflix. He joined Netflix in 2008 as International Development Officer, helping lead the company’s early global expansion efforts.

The password sharing crackdown marked the first major initiative reflecting his systems-first leadership.

Peters had spent the previous decade building the technical and operational infrastructure that made the crackdown possible: the global payments layer, device-ID authentication, and the telemetry stack that defined what a “household” really meant.

With Peters’ promotion, Netflix’s leadership explicitly tilted toward efficiency, monetization, and product optimization — priorities perfectly embodied by the password-sharing enforcement. Within months, what had been a long-running internal test under his purview became the company’s most profitable software update — proof that Netflix’s future would be led as much by product architecture as by programming.

How Netflix Did It (and Why It Worked)

When Netflix launched its password-sharing crackdown in early 2023 — piloting it first in Latin America before expanding globally that May — the company engineered the process with unusual precision to avoid alienating users. Subscribers were prompted to set a “primary household” anchored to their home Wi-Fi network. Any device that routinely streamed from that address was automatically recognized, but if a device began streaming frequently from a different location, Netflix flagged it as “outside the household.” Those users were shown an explanatory screen and two options: request a temporary verification code from the account holder (granting short-term access for travel or guest use), or be added as an “extra member” for an additional monthly fee — typically $7.99 in the U.S., with comparable pricing in other markets.

Each account could add up to two extra members, each with their own profile, password, and viewing history — effectively converting shared logins into lower-tier paying relationships. Netflix framed the change as an improvement in control and personalization rather than a penalty, emphasizing better security, more accurate recommendations, and transparent account management. It also updated help-center materials and onboarding flows to explain how to manage “traveling devices” versus “shared households,” making the rules clear before users risked lockouts.

Defining a “household” required correlating IP addresses, device fingerprints, and behavioral patterns across hundreds of millions of users — all while maintaining privacy compliance and minimizing false positives for legitimate travelers. The rollout touched payments, data science, UX, and global compliance at once — a feat that underscored how deeply Netflix’s operational DNA is technological.

The results were dramatic. Despite some early social-media backlash, sign-ups in the U.S. and Canada spiked to their highest daily levels since early 2020 pandemic levels, according to Antenna, and markets like Spain and Canada saw measurable jumps in paid memberships within weeks of implementation. By combining clear product rules, behavioral nudges, and flexible pricing, Netflix transformed a sensitive feature change into a high-conversion growth engine.

Competitors: Catching Up (Slowly).

Legacy studios could copy the policy, but not the infrastructure or the discipline behind it. While Disney+, Max, and Peacock rent bandwidth from Akamai or Fastly, Netflix moves 300 million hours of video every day through Open Connect: 18,000 servers embedded inside ISPs worldwide. Open Connect, its private Content Delivery Network, gives Netflix cost control, data feedback loops, and reliability no rival can touch. Max and others are still catching up, slowed by legacy systems and fragmented tech stacks.

Disney+ launched its own crackdown in June 2024, a full year after Netflix. In August of 2025, HBO Max said they were in the “First Inning” of the password sharing crackdown and that messaging to consumers is about to get more “aggressive” with the impact starting to appear in its financials by 2026. As of late October 2025, Disney has not yet released specific, granular metrics directly breaking down the impact of its paid-sharing program on subscriber growth. The company has announced overall subscriber gains and mentioned the initiative’s positive effect, but it has not publicly quantified how many new subscribers came specifically from the crackdown versus organic growth. Combining the Disney+ and Hulu services has been cited as a driver of consumer value.

The picture at Amazon is more nuanced. Amazon Prime Video’s posture toward account sharing is uniquely tied to its core business: the Amazon Prime subscription. Historically, Amazon was more lenient, viewing Prime Video as a sticky perk that helped retain members for its more valuable e-commerce and shipping revenue. The entire Prime ecosystem served as Amazon’s “moat,” not just the video service. However, following Netflix’s success in monetizing freeloaders, Amazon began its own shift toward stricter controls in late 2024 and 2025. This included eliminating the old “Prime Invitee Program,” which allowed sharing of shipping benefits with non-household members, and adding specific device limits for Prime Video (e.g., a cap on the number of TVs). This pivot signals that even Amazon is now prioritizing profitability by forcing separate households into separate paying relationships, recognizing the immense revenue potential proven by the Netflix model. It's only just starting, however, so there is no data on results.

The Most Profitable Feature Launch in Streaming History

The password crackdown was arguably the most lucrative move in modern entertainment. A global tentpole like Stranger Things costs hundreds of millions per season — and drives cultural buzz, but its revenue impact fades between releases. Password-sharing reform, by contrast, created permanent margin expansion.

In the first full quarter of enforcement, Netflix added 13+ million new paying subscribers — the largest in company history.

At an average ARPU of $11 per month, that’s over $1.7 billion in annualized recurring revenue with almost no incremental content spend. By late 2024, the cumulative annual revenue lift topped $2.5–3 billion, nearly all profit — the equivalent of launching ten seasons of Stranger Things.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, Netflix posted the largest subscriber gain in its history — 18.9 million net additions — driven by a combination of structural and creative levers rather than any single breakout title. The company attributed the surge to the full global impact of its password-sharing crackdown, which converted millions of long-time non-paying viewers into new paid accounts, as well as the expansion of its ad-supported tier, which attracted price-sensitive users and delivered higher per-subscriber monetization in key markets like the U.S., Canada, and Western Europe. (The launch and scaling of Netflix’s ad-supported tier was another Greg Peters-led initiative.)

Major content events — including Squid Game Season 2, live sports and entertainment specials, and global hits across regions — helped sustain engagement but accounted for only a small fraction of total net adds. Netflix also raised prices in several markets without denting demand, underscoring its growing pricing power and the maturity of its global brand. Together, these factors turned Q4 2024 into a milestone moment for Netflix: record subscriber growth, improving ARPU, and widening profitability — the clearest sign yet that its high-volume, multi-tier strategy is paying off.

Owning the Pipes

Netflix consumes about one-tenth of all global internet traffic, and nearly one-fifth of North America’s prime-time bandwidth. If Netflix still relied on commercial CDNs, it would spend hundreds of millions annually in delivery fees. Instead, it built Open Connect once — and now moves an estimated hundreds of exabytes (1 exabyte is 1bn gigabytes) of video per year at very low marginal cost. Not only did Open Connect provide the data and precision that made the password sharing crackdown so effective, analysts estimate savings of $300–400 million a year in hard expenses, with at least that again in softer value from fewer cancellations and higher playback quality.

Because Netflix owns its network, the costs can be capitalized and amortized over years — turning what would be an expense for a rival into an asset. Disney, Warner, and even Amazon (which does not rely exclusively on its own CDN) write checks each month and call it Opex. Netflix can classify it as an investment; that accounting doesn’t just comply with Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP) — it strategically amplifies its perceived stability, profitability, and long-term value in the eyes of investors.

Netflix capitalizes most content spending as a ‘content asset’ because it owns global rights and expects multi-year benefits. Those assets are amortized over time, smoothing expenses across years — producing steadier earnings even during aggressive investment. The market values Netflix like a technology platform, not a film studio. Smooth margins create perceived stability. Capitalized content builds tangible asset value. Amortization ensures predictability. Combined with recurring subscription revenue, it positions Netflix as a compounding platform — not a cyclical studio.

The Hidden Bet on Live

Netflix’s owned and operated Content Delivery Network (CDN) Open Connect wasn’t just a cost-saving project — it turned out to be a decade-long investment in live. When Netflix built it in 2012, “live” wasn’t even on the roadmap; the goal was bulletproof on-demand delivery. But by embedding thousands of servers inside ISPs, Netflix accidentally solved the hardest problem in live streaming: the edge. The same boxes that cache The Crown can now push live segments to millions of viewers with sub-second latency. When Netflix flipped the switch for the Jake Paul vs. Mike Tyson fight — 65 million concurrent streams by FAR the largest live-streamed audience in history — Open Connect became the invisible arena.

And that ownership marks a real divide. One thing that separates Netflix, Apple, and Amazon from the studios isn’t content — it’s infrastructure. Each built or controls its own global delivery backbone: Netflix with Open Connect, Apple with its Edge Cache Network, and Amazon through AWS CloudFront. That vertical control translates into lower unit costs, faster iteration, and tighter integration between product, data, and distribution.

Traditional studios — Disney, Warner Bros., Paramount, and Peacock— still rent their bandwidth from CDNs like Akamai or Fastly. They pay perpetual tolls on every stream, while the tech platforms capitalize on theirs as assets.

Owning the pipes instead of leasing them isn’t just an accounting distinction; it’s an invisible fault line between old Hollywood and the new.

That same infrastructure gives Netflix a quiet head start in gaming. Open Connect’s thousands of servers already sit inside ISPs, making it uniquely suited for low-latency interactive content. Delivering games — or even hybrid formats like playable shows — uses the same pipes, authentication layers, and adaptive-bitrate logic that power its video platform.

My Prediction: Netflix will announce a dedicated live-content vertical — not just comedy specials or sports experiments; live global concerts, interactive game shows, or international sports leagues it co-owns the broadcast rights to.

Content, Conviction, and Emmys.

Ask an HBO executive why a show gets made, and they’ll probably talk about conviction — a writer’s vision, attached talent, a years-long development process that filters projects in development.

When Netflix greenlit Stranger Things in 2015, it didn’t need to believe it would be a phenomenon. The Duffer Brothers were unknowns; the pitch — “kids on bikes in small-town sci-fi horror” — wasn’t prestige material. But belief wasn’t the requirement. Netflix was commissioning dozens of mid-budget series to fill every imaginable genre pocket — political thriller, period drama, YA romance — and Stranger Things happened to overlap several at once. When it exploded, it validated the system more than the decision.

Six years later, Squid Game emerged from Netflix’s Korean pipeline under the same logic. The budget was modest, the director was respected locally but unknown globally, and expectations were limited to solid regional performance. That was enough. By 2021, Netflix was releasing nearly 400 original series a year — roughly eight times HBO Max’s output. In that kind of ecosystem, every show is a statistical bet. Squid Game became a global hit precisely because the system allowed it to exist. When Disney or Warner Bros. talks about “global strategy,” it’s an initiative layered on top of a fundamentally U.S.-centric model. But Netflix’s platform is global by default: one service, one product experience, 190+ countries. That structure creates a built-in bias toward content that can travel internationally.

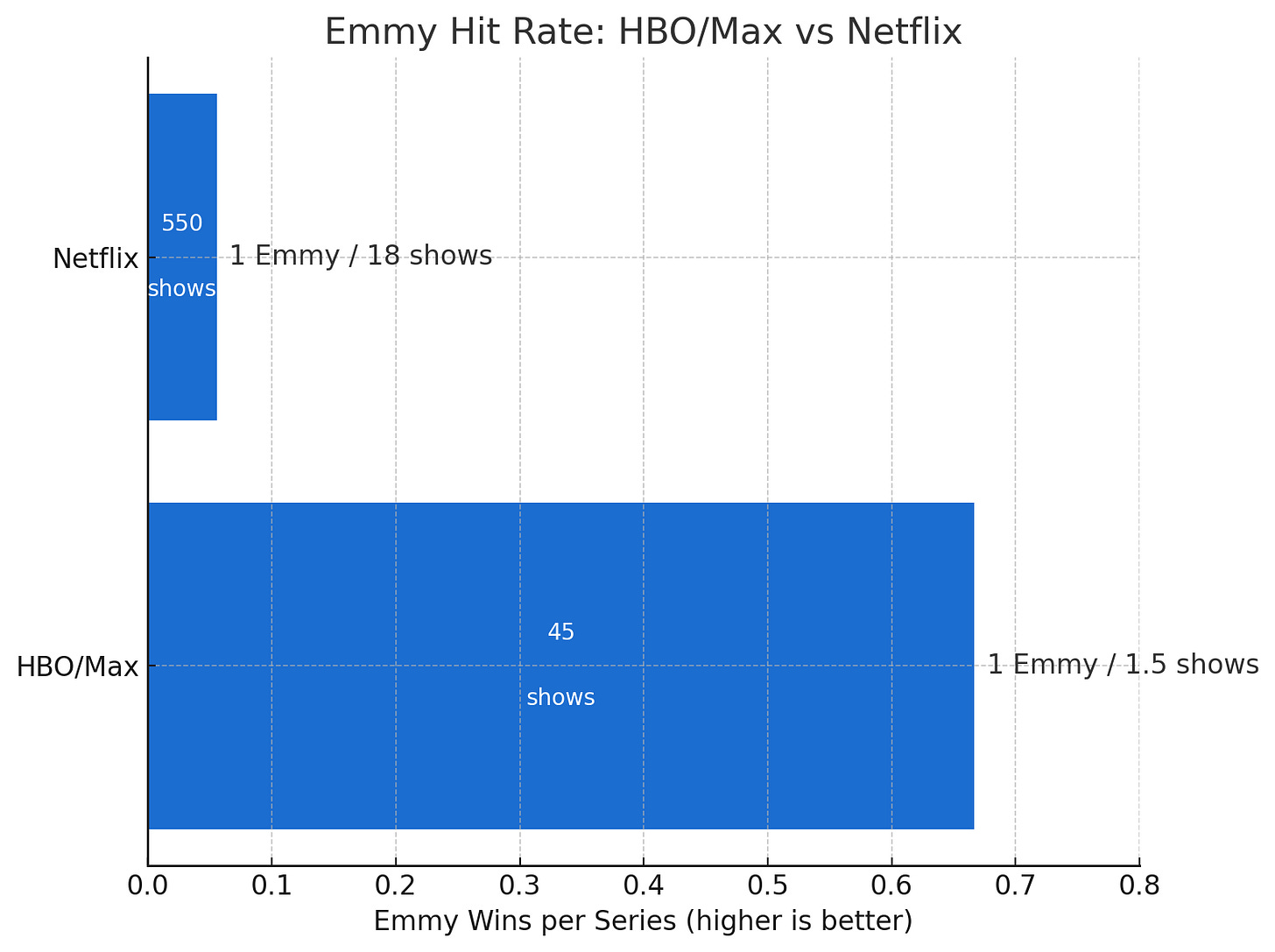

I worked this out after back and forth with ChatGPT, so if someone has better data, please let me know, but based on recent Emmy tallies and release-volume data from Ampere Analysis and trade reports, with about 45 new shows, HBO/Max averaged one Emmy for every 1.5 series — a reflection of its selective, high-conviction approach. Netflix’s 30 wins were spread across roughly 550 new titles, or one in 18. The contrast captures their philosophies: HBO maximizes hit probability per show; Netflix maximizes opportunity surface area.

Legacy television treats conviction as its scarcest resource. Netflix treats scale as its advantage. It tries to make great shows, but it doesn’t rely on greatness alone; it manufactures enough opportunities for greatness to reveal itself. The logic resembles TikTok more than television: where a creator’s clip goes viral not because anyone planned it, but because the algorithm surfaced it to the right audience at the right moment.

That system has a reputation for ruthlessness, but the data tells a subtler story. Luminate found Netflix’s cancellation rate between 2020 and 2023 hovered around 10 percent — middle of the pack. Max’s was nearly three times higher.

Netflix simply produces so much that an average attrition rate looks like carnage.

Dozens of shows are cut each year, but dozens more quietly succeed, often from unexpected places: a Korean survival thriller (Squid Game), a Spanish heist drama (Money Heist), a teen gothic comedy (Wednesday). Scale doesn’t just protect Netflix from failure — it creates the conditions for surprise.

Netflix’s ownership model amplifies that advantage.

Under its cost-plus structure, it pays a premium upfront — typically 120–130 percent of production cost — in exchange for global, perpetual streaming rights. No residuals, royalties, or license renewals. Once a show is made, Netflix owns it outright and can keep it on the platform forever at virtually no additional cost. Even when canceled, those episodes remain fixed digital assets that keep driving engagement without new spending. In the old syndication era, studios needed 80–100 episodes to justify reruns and backend profits; Netflix pre-pays for everything, converting creative risk into a single expense.

HBO, for example, operates under a different logic. Most of its shows are produced or co-produced by Warner Bros. Television, which retains ownership and pays ongoing residuals to actors, writers, and directors whenever a title stays in circulation. That structure allows HBO to license content elsewhere — but also adds recurring costs. In late 2022, Warner Bros. Discovery removed Westworld — along with Minx, Love Life, and several children’s series — from HBO Max as part of a post-merger cost-cutting plan. Variety and Deadline reported that keeping those titles online triggered continued residual obligations and accounting expenses, while removing them let WBD take an impairment write-down and later re-license them to ad-supported platforms like Tubi and The Roku Channel. Where Netflix’s buyout model ensures permanent ownership and predictable costs, HBO’s legacy structure ties every title to a living balance sheet — valuable, but costly to maintain.

Netflix’s advantage isn’t just scale; it’s the efficiency that scale allows for. Prestige franchises like The Crown and Stranger Things get HBO-level conviction, but the rest of the slate functions as an open lab — a creative ecosystem where volume and data produce discovery. In that mix of precision and breadth:

Netflix has built something no one else in Hollywood quite has: a system where accidents can scale, and the next global hit might emerge from anywhere.

Together, Ted Sarandos and Greg Peters form the archetype of a modern media company: art and algorithms, storyteller and systems engineer. Sarandos handles the room; Peters builds the infrastructure moat.

The New Model of Power

Legacy studios still fundamentally believe that producing and owning the right content is their core competitive advantage. It is one of the most important structural differences between Netflix and traditional Hollywood, and it’s still reflected in how legacy studios invest, market, report earnings, and talk about strategy.

In contrast, Netflix treats content as one part of a much larger system — a programmable distribution engine where global reach, data, and delivery infrastructure are the real moats. The competitive advantage isn’t just what Netflix makes, but how efficiently it can deliver, test, and scale that content across a 190-country platform. For Disney or Warner, the crown jewel is a franchise. For Netflix, it’s the platform that turns anything into a franchise if the audience responds.

Following that, most entertainment companies still chase growth through vertical integration — mergers, library buys, co-financing pacts. Netflix has done the opposite. As Ted Sarandos recently said, around speculation that Netflix could be a bidder for Warner Bros.: “It’s true that, historically, we’ve been more builders than buyers, and we think we have plenty of runway for growth without fundamentally changing that playbook.” It’s true that Netflix is interested in Warner Bros. IP, but they already license much of it for a fraction of the cost of buying the whole company. These licensing deals, which often involve fully amortized library content (like older HBO or CW shows), represent high-margin revenue that WBD desperately needs to offset losses in its declining linear TV and content production businesses. Any new owner or CEO would face the same constraints, as halting this high-margin licensing revenue would make it tough to service debt and make any restructuring or refinancing plan hard to pencil out.

Netflix has scaled horizontally, compounding efficiency across geographies and formats instead of accumulating assets. Netflix isn’t hoarding cash for a deal. It’s investing in throughput — more users, more delivery nodes, more global density.

The Sarandos-Peters model works because it acknowledges dual realities — art and algorithms.

Legacy media still treats tech as support, not leadership. Pair a creative CEO with a systems counterpart and you build culture and capability in parallel, not in conflict.

David Ellison told investors in July 2024 that the merged Skydance-Paramount entity must operate as “both a media and technology enterprise,” emphasizing that “the art challenges the technology, and the technology challenges the art.” He described the goal as integrating Silicon Valley-style infrastructure, cloud computing, and AI-driven production workflows into Paramount’s film, TV, and animation divisions.

Perhaps overlooked in the recent announcement of Arena SNK Studios — the new Saudi-backed venture led by Erik Feig — is the telling presence of Andrew Chen of Andreessen Horowitz on its board. Chen isn’t a Hollywood name; he’s a Silicon Valley one, best known for his work on growth theory, network effects, and the creator economy. His appointment signals how quickly the entertainment business is absorbing tech’s mindset: data-driven, platform-aware, and built for scale. It’s the same current Ellison is tapping at Paramount — the idea that the next generation of studios will compete not just on IP, but on technology infrastructure.

The future isn’t empire-building. It’s horizontal scale and leveraging data— growing and connecting audiences across devices, languages, and formats.

Netflix’s head start is enormous, but it’s a design that can be emulated. The company didn’t build better shows; it built a better system for making, moving, measuring, and monetizing them. That system can still be studied, adapted, and localized by anyone willing to see that, besides storytelling, engineering, accounting, and system design are now core competencies in the industry.

The media business still loves writing about the mogul. David Zaslav’s party at Cannes and the kerfuffle around TCM probably generated more press in the industry trades than Netflix’s tactics on cracking down on password sharing. It is unlikely we will see David Ellison or David Zaslav adopt a dual-leadership structure with a systems-focused co-CEO, as Netflix has done with Sarandos and Peters, but that might be the boldest move they could make.

What if the real leverage in twenty-first-century entertainment belongs not to the dealmaker, but to the engineer optimizing the stack?

Such a minor follow up question in relation to the major quality and breadth of this article (which, thank you): I am curious based on your last paragraphs, could it be said that scale and growing audiences is part of Ellisons plans through OpenAI, or even acutely the adoption of alternative subscription based acquisitions, like Free Press?